Fireside Chat: Ending AIDS as a Public Health Threat by 2030 and Beyond

In a Fireside Chat session preceding the Continuum 2024 conference (June 9, 2024), three thought-leaders discussed the trajectory of the HIV response through 2030 and beyond. Co-hosted by IAPAC and UNAIDS, the conversation offered unique insights into barriers, challenges, and opportunities to achieve a sustainable HIV response through 2030 and beyond. This transcript has been edited for clarity and conciseness, ensuring that the integrity of the panelists’ original messages remained intact and properly contextualized.

Dr. José M. Zuniga (IAPAC): Welcome to this Fireside Chat at IAPAC’s Continuum 2024 conference. I am happy to co-moderate this conversation with my friend Vinay Saldanha, Director of the UNAIDS Washington, DC, Liaison Office. We are honored to have with us three distinguished thought-leaders who are at the forefront of the global HIV response: Dr. Angeli Achrekar is Deputy Executive Director of UNAIDS; Dr. Meg Doherty is Director of the WHO Department of Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programs; and Dr. Yogan Pillay is Director of HIV and TB Delivery at the Gates Foundation.

As we convene for the Continuum 2024 conference, our goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 is beset with significant challenges. To be clear, we have made remarkable progress in the fight against HIV. Today an estimated 29.8 million people are on life-saving antiretroviral therapy, or ART, which is a testament to global commitment and collaboration in addressing the HIV epidemic. The scale-up in ART coverage has been instrumental in averting AIDS-related deaths, but not enough of them. The fact we had an estimated 630,000 AIDS-related deaths in 2022 speaks to the challenge of reaching all people and communities everywhere to guarantee them a near-normal lifespan and achieve U=U [undetectable equals untransmittable].

An additional and consistent challenge is that HIV incidence remains unacceptably high, indicating the urgent need to intensify our combination HIV prevention efforts. While ART has transformed the lives of those living with HIV who have achieved U=U, we must also surge our strategies to prevent new HIV infections through comprehensive approaches, including equitable access to PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] in all its various dosing and delivery modalities for all people, everywhere.

Our conversation today will explore the multifaceted strategies needed to achieve our 2025 targets and Sustainable Development Goal [SDG] 3.3 by 2030. We will discuss progress, challenges, innovative approaches, global collaboration, and sustainability beyond 2030. Without further ado, let us look forward to a meaningful and inspiring conversation. I would like to invite Vinay up to say a few words and open the conversation with the first question.

Mr. Vinay Saldahna (UNAIDS): Good morning, everyone, and special thanks to José and the amazing team at IAPAC and the Fast-Track Cities Institute for convening us for this amazing conference, Continuum 2024, and for this important pre-conference Fireside Chat with our three global HIV and health leaders.

As José has already framed the discussion today, of particular concern is that the international community came together at the high-level meeting at the UN General Assembly in 2021 to set a series of extremely ambitious targets that need to be reached by the end of 2025, and a lot of focus, of course, rightly is on the 95 targets. Hopefully, in today’s conversation we are taking it a step further and really focusing on not only how we close the really acute gap between [where we are now and] where we need to be by the end of 2025, but also how countries and all communities can be supported on a path to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 and sustain that progress beyond 2030.

That is not only a concern because we have less than 20 months between now and the end of 2025 to report on. We must really take stock of has the international community and every country and every community made progress as committed to in 2021 and towards the 2025 targets? Also, what are the changes, what are the innovations, [and] what are the new approaches that are needed to maintain and accelerate that progress and sustain that progress to 2030 and beyond? In that respect, it is an honor to welcome our three esteemed experts in global health and HIV leaders to lead today’s discussion.

Our Fireside Chat is not going to be a formal series of presentations, but really an interactive discussion about how these three global health and HIV institutions complement each other’s work. What is the vision we are seeing for accelerating progress and maintaining and sustaining that progress to 2030 and beyond? I would like to start [with] Angeli Achrekar, the Deputy Executive Director for Programs at UNAIDS. [Can] you provide us with a short summary of the key issues that you are seeing in this context?

Dr. Angeli Achrekar (UNAIDS): Thank you so much, Vinay. Thank you, José. I will just say a few words about what we do at UNAIDS. I have the privilege of serving, as Vinay said, as the Deputy Executive Director for Programs at UNAIDS. UNAIDS is the only joint program in all of the UN that brings together 11 different UN agencies around a common mission; a mission to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. We are so privileged to be able to work together with multiple sectors across the UN, but across the countries as well.

WHO is one of the critical partners in the joint program , as are UNICEF, the World Bank, UN Women, the International Labor Organizations, World Food Program, and many others. Which really exemplifies what the AIDS response needs, a multi-sectoral approach to end AIDS as we know it. At UNAIDS, we serve as an orbited body bringing together the broader global targets that were mentioned earlier, and then the [UNAIDS] Global AIDS Strategy [2021-2026]. We work =with countries to ensure that countries are moving toward achieving those targets, that they then have national strategies that are adapted from the targets to be able to achieve those. Setting targets, working with countries to help them accelerate against those targets so that ultimately, we can have the greatest impact around the globe.

Mr. Saldanha (UNAIDS): [Let us] ask Meg to deliver short opening remarks on behalf of WHO. Dr. Meg Doherty is internationally known as the Director of the Department for Global HIV, Hepatitis, STI Programs at WHO. Meg, please, over to you.

Dr. Meg Doherty (WHO): Thank you, Vinay. Thank you, José. WHO, as you may know, is responsible for the health sector response. As a co-sponsor for UNAIDS, we also have a health sector strategy. My department has a broader mandate looking at not only HIV, but also hepatitis and STIs, and what we see in terms of cross-cutting nature of some of these infections that are being transmitted often at the same time as HIV, but also the end users, people affected by HIV may also be affected by hepatitis and STIs. We see our role as also looking at the broader health sector goals of achieving Universal Health Coverage. If you follow any of that work, you may know that we have SDGs to reach by 2030. Having access to Universal Health Coverage is one of those important pieces, and we are off track for that… We are also working to [identify] the services where HIV can contribute to achieving those goals. To be honest, the delivery that has been happening around the HIV program around the world is one of the strongest elements of the SDG responses. To me, all your work is contributing to helping the world achieve the SGDs.

We just came out of the World Health Assembly. You probably are aware the world is much more complex than it was 40 years ago or 20 years ago when PEPFAR started. We were not looking at a lot of challenges with climate, challenges with, one would, say conflict. Our job is also to report on the indicators across the three areas [HIV, hepatitis, and STIs] and across the commonalities of how we can deliver together. Sustainability and primary healthcare are some of the issues that we are taking on in terms of looking towards the future for HIV care [that is] accessible to all.

Mr. Saldanha (UNAIDS): Thank you, Meg. Our third panelist is Dr. Yogan Pillay. Yogan is a very dear friend and colleague and, of course, today representing the Gates Foundation. Yogan is also really a very precious leader in the global HIV response. There are many people responsible for the amazing state of the ART and the continuum here in South Africa. If there is one person who really should take much deserved credit for showing to the world that you can scale up from hundreds of thousands to millions of people living with HIV on ART, and scale up the U=U message across districts and counties, that was the amazing pioneering work Yogan advanced as the Deputy Director-General for Health for South Africa’s Department of Health. Yogan, welcome and please describe your vision as the new Director of HIV and TB Delivery at the Gates Foundation.

Dr. Yogan Pillay (Gates Foundation): Thank you, Vinay, and a word of thanks to José as well for this kind invitation. We really need to focus not only on the [95-95-95 targets], which are very important, but possibly now the 98s because 95s I do not think are going to get us where we need to be. Second, we need to focus on the 90% reduction in new [HIV] infections relative to death. Again, we are not anywhere close to reaching [that level of reduction]. Now, as Gates Foundation, we are essentially a funder of innovation. We cannot take anything to scale with the small amount of money we have as a foundation. That is where the role of WHO as well as UNAIDS, which works at country level, across UN agencies, and with governments, is very important. As well as, of course, the Global Fund [to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria].

I have been in my role at the Gates Foundation for 13 months leading the HIV and TB delivery unit at the Gates Foundation. One of the things we are looking at is what does the changing nature of the HIV epidemic mean for delivery? How do we need to change the way we think about delivery? What innovation do we need to think about and how do we first show proof of concept and then work with our partners to take into scale? It is very clear that doing the same things in the same way in many countries where the epidemic is changing quite rapidly will not get us where we need to be, so we need to think slightly differently about how we do that. We are here, and I am here, to hear new ideas around innovation and delivery taken up so that I can learn a few things before our next stage.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): We will start with the moderated discussion now, and my first question is about how we accelerate from the incremental progress we have achieved so far to get to the end of AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. What concrete actions should we take? But, before that, what do we mean by “ending AIDS as a public health threat”?

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): When we talk about ending AIDS as a public health threat, [it is in relation to] SDG 3.3, with associated targets to which every country has agreed. Then there are 2025 targets, which are the milestones for getting us to get to 2030. What we are talking about in this context of still not having a vaccine or a cure, is that there will continue to be new infections. There will continue to be AIDS-related deaths. What we are talking about overall is a reduction in new infections and AIDS deaths by 90% from their baseline at their 2010 levels. Now, that then translates into several different targets, both treatment targets, yes, the 95-95-95 targets, but also prevention targets – very precise prevention targets.

One thing I will just note related to the targets is that we can have all the best biomedical solutions in the world, but if we cannot help to address stigma and discrimination, societal barriers, inequalities, and other such barriers, it is all for naught. We are seeing a backsliding of the HIV response because we are not addressing all of this holistically. In terms of maintaining momentum and progress and question what can we do to really, really accelerate? It is upon all of us, knowing that the 2025 targets are literally right around the corner, and that we are not where the countries, all of us, the globe, we are not where we need to be, to do something different. We all need to be accelerating and pushing in ways that we have not before. The thing is, we know what needs to happen. We know that there needs to be strong political will at a country level to really focus on the response. We know that there needs to be evidence-based or data-driven intervention that happens as granularly or as precisely as possible at the subpopulation level, at the subnational level, so that we are really addressing what is happening at the most local level. We know that we need to tackle those barriers that I mentioned earlier. We need to ensure that the enabling environment is such that it is promoting services and service delivery. We need to really push for more simplified service delivery and more engagement with the community in ways that we are reaching these populations where they are. I am most concerned really about the 2025 targets that are right around the corner, and we still have a way to go.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): Meg you also commented on how to get the balance right. We continue [to achieve] incremental progress versus breakthrough progress and playing off 2025 versus 2030.

Dr. Doherty (WHO): Sometimes we say many of the same things over and over, that we need to do more, but we also see that we have perhaps less and less resources or less motivation or more things challenging the health sector or the world, in general. I have seen over the last couple of years an example that we are working on triple elimination the mother-to-child transmission, where countries have become reinvigorated and engaged around the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, hepatitis, and syphilis.

Now we have a couple of countries from Africa that are making quite a bit of interest in putting dossiers for this elimination. I feel like stepwise, and stepwise where there is an opportunity to have some congratulatory feedback of achieving some of these hard-to-reach targets, such as the elimination of mother-to-child transmission. I also believe that we should [celebrate] the countries that have done well. There are about five countries that have reached the 95-95-95 targets, another six that should probably reach [them] by 2025. Let’s congratulate them, [and try] to ensure that they keep that governmental support for what they have done well.

I also feel we need to identify the countries that are so far behind, that have not reached 50% antiretroviral coverage yet, but have a relatively significant burden. There are countries in the Americas, there are countries in Asia, and I think it is going back to some of these structural issues, that perhaps that population is hard to reach [in these countries]; key populations, people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, transgender people. So therefore, [these countries] are not achieving that same ART coverage hat we would like to see to be able to have people live healthy, quality lives, far beyond viral suppression. I would like us to see how countries that have not done well, how we can help elevate them, and I think that is something we do not always do. We do not always say we are going to work with these other countries that have not done well and try to pull them up to reach at least the 2025 treatment targets, treatment coverage of over 75%. We know from the modeling for ending AIDS as a public health threat that if we cannot get over 75% to 80% rt coverage, we will not achieve prevention and reduction of incidence in death targets. I hate to say it is one intervention, but it is one plus many so that ART can be accessibly reached.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): Before we move to Yogan, I ask you to dig a little deeper. Many of us, at the conference and in our daily work, are focused on HIV. You have talked about “triple elimination.” Can you just clarify what you mean by triple elimination?

Dr. Doherty (WHO): It could be quadruple or triple in some countries, but triple elimination is achieving targets and goals that could be certifiable by WHO of achieving reductions of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B, and/or syphilis, and/or, in some parts of the world, Chagas disease, or HTLV 1, from mother-to-child. It is achieving levels of very, very low transmission, because the mother receives prevention treatment, and the infant receives some prevention as well. Really, [triple elimination] is a way to stop new infections.

Dr. Pillay (Gates Foundation): The one thing I want to say is that I do not think our health systems are geared to go the last mile. If we are going to depend on our health systems to get us to the last mile and over the line, I fear that is not going to happen. We have got to think about new systems of delivery, and it must include co-creation, co-production with communities that we are leaving behind as a health system. They are not being left behind. We are leaving them.

We have got to figure out how by co-producing, co-creating these systems, different types of health systems, we are able to reach people we are currently, as a health system, not reaching. Even in countries that have not reached the targets and public health goals it is not because the health systems are weak, and the current environment, asking ministries of finance to give health departments, ministries of health more money, is probably not going to be of any assistance. We have got to figure it out, and I hate to use the “efficiency” word, but we have to figure out efficiency, and improve efficiency, but we have to also change our delivery systems.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): Innovative approaches and long-acting injectable technologies are a centerpiece of the Continuum 2024 conference, with a focus on leveraging cutting edge technology to make sure we can optimize the continuum through their use. How do we scale up access to and use of these approaches and technologies equitably? What steps can be taken on the financing side? How do we roll those expenses into health budgets?

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): What is exciting is that there continue to be more and more new technologies that are available. They could potentially be extraordinary game changers in the HIV response. Particularly, if we are thinking about how countries can sustain the HIV response into the future, and then some of these long-acting injectables are quite extraordinary. It all does come back to, I would say, access, access, access. If we cannot, as a global community, ensure that the costs of these new innovations are affordable for those who need them most, then it is as good as what I said earlier.

We have the best technology in the world and the people who need it most cannot access that [technology]. We must continue to work together as a community, private sector, public sector, and across all the organizations that you represent, that we represent, to find ways to make these new innovations more accessible. The flip side of that coin is also, are we working together with countries to ensure that the policy environment is suitable? To make sure that those innovations can be accessed by the populations that need them most. Are the policies in place all the way down to the community level to make sure that whether it is long-acting or whether it is in the world perhaps for adolescent girls and young women for example, are these policies in place so that key populations can access them? The third piece really comes to the point that Yogan was just making around thinking about service delivery differently. A part of the way we need to be thinking about service delivery differently is precisely around how we are engaging communities in service delivery in perhaps different and more pronounced ways than they have been. We know from the HIV response, in particular, how critical community is in service delivery. We saw how important the role of the community was in making sure that HIV prevention and treatment services continued in the wake of COVID-19. Community is instrumental. I will just say it is all about access, access, access.

Dr. Doherty (WHO): I want to go back just a moment, to one of my mentors, people may or may not remember him, but John [G.] Bartlett was a huge name in the early HIV field from where I trained [at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD, USA]. He would say to me, “Can you envision a world where you could just put on a watch, get a little dab of blood, like glucose, glucometer, and know your viral load? Know what you need to do, have everything you need to do to take care of yourself, living with HIV, at home, when your treatments are there?” This idea of self-care and organizing oneself about around your own treatment and understanding how to monitor, like monitor a glucose, monitor our load, or ensure that you can live your life and have two months free from pills. It is really, really enticing, and I think it is the future. I think, too, about wearable tech and wearable healthcare promotion products.

On the flip side, we have an issue with what has been so successful to get nearly 30 million people living with HIV around the world on ART. That is because there was this huge reduction in price for the current best treatment we have, which is dolutegravir. Around the world people can pay as low as USD $35 a year. Think about that… In the United States, [the cost] is thousands of [US] dollars. In many parts of the world, people are not paying more than USD $50 more for a year’s worth of antiretrovirals. For PrEP, it is the same. It may be USD $20 to USD $30 a year. Innovation is important, and we have to do the work to bring those prices down for the innovations that are coming. I do think self-care is the future, injectables will be helpful for some, but we cannot pay USD $1,000 and scale up for the millions of people who need [prevention or treatment]. Whatever we can do with pharma, with industry, with generic companies, to ensure that injectable PrEP and injectable long-acting ART are the same prices or nearly the same prices [is critical], because, at some point, it will be economies of scale. Do you invest in oral medicines to reach more people, or do you invest in an injectable regimen and reach fewer people? You do not want to have to make that uncomfortable choice. How do we get the best injectable treatments to be at a near similar price for the oral medicines? We know it is doable. It just takes a lot of people thinking hard about it, working with the companies, working with generics, and pushing the envelope for global public health.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): How does the Gates Foundation see this? Because many of us took note of a very public campaign that was launched in the last couple of weeks, pushing Gilead Sciences to consider pursuing a voluntary license through the Medicines Patent Pool for lenacapavir while it is still only now moving into the pilot trials for PrEP in the United States and elsewhere. This is something that the community is already asking Gilead Sciences and other private-sector pharmaceutical companies to think about moving on when the price differences that Meg and Angeli already talked about are just so profoundly inhibitive. It is very difficult to consider how you introduce a range of long-acting injectable products for PrEP. Also, [in relation to] antiretroviral treatment, how is that going to be sustainable, accessible, and affordable over the long term? How do you see the Gates Foundation continuing to play a leading and innovative role to help this process?

Dr. Pillay (Gates Foundation): I can say the [Gates] Foundation has been very engaged with Gilead [Sciences] for quite some time now, even before I joined the team. We have common goals as a foundation with Gilead Sciences to try and figure out how to move it along, both in terms of volume as well as price, because it is one thing to get the price down, which is fair, as both Angeli and Meg mentioned. We also need the volumes. If we do not get the volumes, we are going to be then prioritizing certain groups. That might be a good thing because it might lead to those that most need it getting it first.

My concern about that [scenario] is that it might stigmatize problems like we have seen previously with other products like oral PrEP, for example. We should also not forget that oral PrEP works and that we should not give up on it. There might be large numbers of people that still prefer oral medication. That is one of the reasons that the foundation is also looking at MK-8527 [oral nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI)] as another option. What is key is to ensure that we give people maximum options, but at the most affordable prices for them as individuals as well as for the country.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): I have a quick follow-up, and then I will ask the next question. In the United States, we reviewed AIDS Drug Assistance Program data around the specific percentage of people who switched from oral to injectable ART, and we found out it was about 10%. Are you concerned about pushing too hard on long-acting and disincentivizing companies from continuing to market oral PrEP, at least until and if ever the oral option is proved inferior? Is that a concern of yours? I ask particularly with respect to patient choice because they should have the autonomy to select oral versus injectable and not have that decision made for them de facto.

Dr. Doherty (WHO): To be honest, I am a little worried that there is going to be a sense that injectables are better than oral. Where we are today is because we have really simplified, optimized oral medicine options. I also get a little worried that the pharma companies do not seem to have a very deep pipeline of new oral medicines coming. I also know that if you took a survey of people taking pills or injections in this room, you are going to get very different views. Some people would prefer to stay at home taking a pill for their medicine daily. Some would prefer an injectable. That element of choice is important, but it may be counterproductive to a public health response.

We have done so well because we were able to have so many millions of doses of oral treatment available for everyone who needed it. Right now, the injectables are not available for everybody who might want them. Not only can there be stigma, but there could be a sense that yes, only certain people with needs will have access to [injectables]. Right now, I know, for example, in the United States, these drugs are very well marketed, and there is a lot of transition happening. That is good because it is going to give us more evidence about how the transition works. If people like them over the long term, can cost reduction happen? I think there are going to be other innovations that become available in the future. If a patch has your ART, if you have other approaches, we need to be open to all those approaches that come, but be looking to survey everyone who needs it, not just the small minority.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): Angeli, Vinay mentioned your previous leadership role at PEPFAR and the current work you are advancing to influence PEPFAR decision-making as well as, for instance, the Global Fund’s decisions, too. How do we effect changes and innovations to enhance the effectiveness of both PEPFAR programming and program funding allocations from the Global Fund?

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): All three of us have had the privilege of working very closely with PEPFAR and with the Global Fund, particularly as implementation happens at the country level. What is going to be important as PEPFAR and the Global Fund think about the future, as we are collectively thinking about what it is going to take more countries and communities to sustain the HIV response into the future, is to come back to some of these topics we are talking about here, simplified services. What does that look like? What does that cost?

What we have been supporting with PEPFAR and the Global Fund was really coming at the HIV response from an emergency perspective. The approach was whatever it took to get the job done, but the HIV response is very different now. If we are not in an emergency state in the way that we were 21 years ago when PEPFAR was launched, for example, I think PEPFAR and the Global Fund need to be evolving with their service delivery, with their approaches that are aligning with what we are talking about here, more simplified service delivery, more approaches that really involve communities in engaging in the response, and self-care. These are different ways that our global response is going to have to evolve.

I think what is exciting about it per se is the Ambassador [John] Nkengasong at PEPFAR who is leading the effort right now, and Peter Sands [Executive Director] at the Global Fund, they are both very keen on working together with us, with countries, with communities to help shift and evolve their responses so that they could support the countries in this evolution toward what it is going to take to sustain the HIV response.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): Do you fear that we could wind up back in an emergency HIV response?

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): I do fear that we could wind up back in an emergency response and lose the gains that have been made. Everyone here has talked about the gains, [which have been] unprecedented. The AIDS deaths have declined by nearly 70% since their peak. New HIV infections have declined by nearly 60% since their peak. The gains are extraordinary. Five to six countries have met their 95-95-95 targets, and a whole slew of other countries are on their way.

We have also seen that these gains are fragile. We have seen how quickly in situations, for example, where certain key populations have been robbed of their rights to access health. We have seen direct impacts very quickly on how that translates to HIV services. For example, in Uganda, with the Anti-Homosexuality Law, we have seen the impact of some of these larger poly-crises. Climate change, its impacts on health. We have seen what it has done in Kenya and Mozambique and elsewhere. We have seen some of the impacts of COVID-19 and what it has done to the HIV response. Yes, I think if we lose our focus on the HIV response and if we do not continue to tackle it with the focus, the strong need to continue to get to these targets, I believe we will get back to that place where unfortunately, all those gain we have made will be unwound and we have to continue to start back where we started.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): Yogan, I would like to turn to you for a second on the issue of collaboration with PEPFAR and the Global Fund. The Gates Foundation was one of the early investors, again, and supporters of the Global Fund. You maintain an active relationship in Global Fund governance and support even financially contributing to the life-saving work of the Global Fund. How is the foundation seeing the goal of particularly the Global Fund at a time when the foundation is clearly, I would not say expanding, but highlighting its engagement and financial support across several issues in a complicated world? The team at the Gates Foundation, led by you, are essentially keeping that focus on HIV, keeping that focus in global health. How do you see that engaging generally from the Gates Foundation and particularly vis-à-vis the Global Fund itself?

Dr. Pillay (Gates Foundation): As of now, I can say that the foundation is heavily invested in both HIV and TB because of the programs that are responsible for, at least, on the delivery side. We are fully committed to support UNAIDS. We were quite worried about the potential impact of decreased US government funding to the Global Fund replenishment. We are working quite closely with Meg, Angeli, the PEPFAR team and the Global Fund teams to try and think about what does sustaining the HIV response, not only to 2030, but beyond, means.

We have been digging into the current funding arrangements. We have been digging into efficiencies. We have been digging into what countries can bring to the table in terms of domestic financing, which for some countries is rather limited. If you take Malawi, Zimbabwe, among other countries, for example, without Global Fund and PEPFAR support, we cannot talk about them sustaining an HIV response. We have some really hard questions that we need to try and answer, which means that we might have to go back to rethink what we prioritize. When we had more money and when it was an emergency, we tried to do everything for everyone, but going forward, my fear is that we may not be able to do everything for everyone, which means we will have to make some very difficult and hard decisions, and we should be planning for them rather than having them thrust upon us.

With the Global Fund, it is very clear that countries decide, and depending on how the CCMs [country coordinating mechanisms] are arranged, you might get a different priority set of priorities. Often, it is the right set of priorities, but sometimes, they are not effective. We need to figure out how we can leverage countries, country leadership at all levels of the country, to make the right decisions. Now, one of the things I think we need to invest in is data. Data collection, data mining, and data groups to make those decisions, because if we do not, then we may make the wrong decisions in terms of setting these priorities, but communities must be integrated in data activities. We would like to see the Global Fund working with countries, looking at the quality of the data, looking at the breadth of the data, and looking at what is being prioritized and what is going to be relevant.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): Meg, I would like to turn back to you for a moment regarding how WHO leadership sees the continued focus on HIV. Of course, many of us tried to keep up with the dizzying number of engagements and side events during the recent World Health Assembly. At UNAIDS, we are very impressed and reassured to see how the Director-General [Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus] allocated much needed emphasis and focus on HIV in support to the World Health Assembly, and there was an agenda item specifically on the Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV and STIs and Viral Hepatitis. At a time when there seems to be so much focus on carbon emissions and negotiations around the pandemic accord, how do we make sure that WHO’s leadership can focus on HIV and on the progress that needs to be made on HIV does not get paused when there are so many shifts happening?

Dr. Doherty (WHO): That question is my psychic challenge every morning, how are we going to manage this in a world that keeps changing? In the conversations that we have just had, I keep thinking about what is different and unique about HIV that we can never forget, and I think all of you have dedicated your lives working on HIV because it is specific a virus that without treatment will kill a person. It is deadly. It can affect people at all stages of their lives and people can live with it without knowing about the virus. Now, we have many other viruses like that out there, but either they have a vaccine, or they have a cure coming down the pipeline.

For HIV, we have neither the cure nor the vaccine. I think that is important, and then it is transmitted sexually, and so there are many reasons why people do not think about it and do not want to be open about it and there is stigma and discrimination regarding all of this. From our perspective, it is just about being there in the World Health Assembly, constantly reminding the health leaders [that if] we do not keep doing what we have done so well, it could easily come back, and we have seen some examples in countries where they have not had strong HIV responses where we have had outbreaks of HIV when nobody needed to have that outbreak. We knew what to do but the country had not set up a system to monitor the data and to do what was necessary to avoid infections. That is the world we might be living in if we do not keep this on the agenda and really get us towards those targets. If we can get us to the targets in 2030 and help the countries who have not invested, perhaps at some point, we can be a little bit more relaxed about having an endemic disease with people living with HIV, accessing what they need, and really, introduction of new infections so that we are in the reduction of deaths because we are getting the full spectrum of care needed.

Our recent report highlights where we are towards the 2025 targets, but across three areas. HIV certainly is doing better than, say, hepatitis or STIs, syphilis, for example. We have seen with the public health systems in the United States and the Americas, and other places, broke down during COVID-19, we saw a surge of syphilis. We know that without a constant public health response, viruses, bacteria, et cetera, will surge. Just to say, my sense here is that we have to keep it on the agenda. Countries brought it to the agenda, and we had at least 15 or 20 countries say this is still a priority for them. That is good to hear in a world that is very complex with emergencies. The other thing is when the emergency team [at WHO] needs help in working with communities, speaking about messaging, risk communication, community engagement, they do not go to another department, they come to our [global HIV, viral hepatitis, and STIs] department. We are actually part and parcel of the emergency responses for PEP, for Mpox, for COVID-19. Our teams have been engaged in all of that. Outbreaks of HIV in Pakistan, outbreaks of hepatitis here and there, we are fully engaged because the skills that the HIV community have developed over these years are integral to everything else that the World Health Assembly is trying to track.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): Yogan just referenced, or alluded to, the idea of finding ourselves in a situation where we are actively rationing HIV care, which is a nightmare scenario. In that respect, Yogan, from the perspective of your previous life in South Africa with the Ministry of Health, and Angeli, your role in pushing for investments in HIV, how do we tackle the complacency we are experiencing currently in the finance space and mobilize greater resources for both domestic and international sources so that we continue the momentum we managed to achieve despite all these other barriers, like COVID-19?

Dr. Pillay (Gates Foundation): It is all about investments. I think to everyone’s surprise, the only cost-saving intervention is condoms. Last but not least, or almost last, is CAB-LA [long-acting cabotegravir]. Countries will be forced to, I would not use the word “ration,” even though I know that is what we all mean, right? I would use the word “prioritization.” The way it needs to be prioritized should not be top-down government decisions, but it has to include the affected communities.

I will tell you another story, José. When I was still in the Ministry Health, we did this long investment case study on hepatitis. I took it to the policymakers. We said, “Look, it is brilliant.” This was now more than eight years ago. I then went to our national Treasury, and I said to them, “Well, doctors say it is cost-saving. Can you give us the money?” They responded, “Go find the money with the private sector.” The consequence of all that is that there is no hepatitis program. It is a hard sell, and in the context of sustaining the HIV response, we have got to do the work now.

If we wait any longer, we are going to run the risk of having significantly underfunded programs where we need them most. The fire you guys have lit at this fireside chat is real, we have got to get going more rapidly than we have. Some of us have been working with Ambassador [John] Nkengasong on the sustainability issue, but I think we are moving at a glacial pace relative to the task at hand. I think we really got to accelerate significantly, or we are going to be landed with many countries sliding significantly back. Remember, we have got almost 30 million people on antiretrovirals. By 2030 and beyond, we are going to have much the same number of people or more on antiretrovirals and we have got to keep the adherent. Because it is an aging cohort, they are going to have diabetes, hypertension, or cardiometabolic conditions that typically come with aging. It is going to be much more complex to treat and manage people living with HIV in a few years than it is now. Our health systems, frankly, are not prepared.

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): I will just emphasize a couple of points and add a little bit to complement. One, that the urgency Yogan described so well, the urgency of now, is so important. There are still 9.2 million people living with HIV who are not yet on ART. We still have 1.3 million new infections that are happening every year. If you are even thinking about the cohort that you are going to need to look after well into the future, it may even be more than 30 million people that are on ART. It is going to be much, much more complex because what is not stopping are all these other complexities that Meg was talking about, as well, with climate and war and conflict. There may be two things that I would add to this conversation. One is around the choices that Yogan was talking about… Sometimes, we come to a point in the response where we cannot do everything for everyone, and we have to be very precise. We, meaning the countries, have to be very precise about, if they have a dollar, where it is going to go. Where are they going to have the impact that they need to have? Not just for now, but how is this going to impact their [national] epidemic into the future?

These are questions that need to start being asked right now. Related to that, it is not always the most expensive innovation that is the best option. We have to look at all the different kinds of options that are out there. Meg, you were talking about oral PrEP. We still have not scaled up oral PrEP to the targets at all. The second point that I would say, José, to your question, is all of us, the HIV response, we are sitting on something or have been privileged to be a part of something that is extraordinary. The HIV response has shown that it can deliver on HIV outcomes, but it can also deliver on so much more. Of all the SDGs, 17 of them, the only one that is tracking in the right direction is SDG 3.3. That is because of the HIV response, [which] has shown that it links not only to HIV outcomes, but also to gender inequality, to economic empowerment, to child immunizations, to other things, and so much more. We have to continue to lean on what we know to be true and build upon that and show the world that by realizing and leveraging this response in different ways, probably in evolved ways, we can do so much more.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): I would like to return to one of the issues that has already come up, and that is specifically about HIV prevention. It has been mentioned by a few of you that the world is making progress towards 95-95-95. Some countries are near, and some countries are making very slow progress. But still, generally, the scale up of testing, treatment, viral suppression, and it is linked to new U=U is a very positive and very inspiring impact to encourage other countries and communities to follow that lead. We are also seeing progress in HIV prevention, though it is much slower. How do we focus on making breakthroughs, not just accelerating progress, but making breakthrough progress and not putting all the eggs in the basket of a long-term objective? What are some of the practical things that we need to do now, specifically on turning off the tap of new HIV infections, and not just accelerating, but making breakthrough progress in HIV prevention?

Dr. Pillay (Gates Foundation): This is probably one of the hardest questions to respond to. We as the [Gates Foundation] convened a workshop in early December [2023], trying to answer the question around what does reimagining HIV prevention mean? We had a lot of brave people, about 30 or so, and we defaulted to what we are currently doing. Looking for that holy grail is probably not what we should be doing. We should be doing the basics. What did we default to? We defaulted to making condoms not only available, but usable, because female condoms right now are not very usable.

When I was in the [South Africa] Department of Health, I made a big push to get 40 million female condoms, against almost a billion male condoms that we made available just for South Africa. The uptake and communication around this were very, very difficult. Now, it is gone down to about 10 million female condoms being produced. We want to do better at doing the basics. We stopped communicating around HIV. The current generation, the 15- to 20-year-olds, have not seen people die of [AIDS-related complications]. They do not understand the impact of HIV, as the cohorts that are 30, 40, 50 years old. We are not communicating. To their credit, they are doing much better than previous cohorts in terms of new infections, but we are not doing good. What we are seeing now is that the new infections are getting later and later. We are finding new infections in the 25, 35-year-olds. We need to figure out where the new infections are coming from and what to do about it. It is back to “know your epidemiology,” “know where your new infections are coming from,” and focus on them.

Dr. Doherty (WHO): What I have seen also is not only that condoms are out of favor, but we do not talk about condoms. Condoms are essential for our STI prevention. We need to bring that message forward. We can put this in the context of many things. I have a young son, and the idea of getting an STI is worrisome or getting somebody pregnant. Using that language with young people around why a condom is important could be useful. Young people [do not] hear the message around HIV or STIs very often anymore. That is [an issue around which] we can do more education.

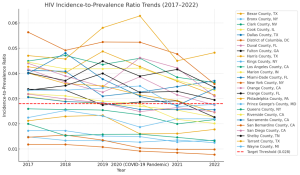

[There are] some innovative countries that are looking at the ratio between prevention coverage and treatment coverage as the magic ratio, that if you can do this well, you can really start to decrease new infections. This is what happened with Sydney, [Australia], which came out in 2023, stating that they felt they had virtually eliminated sexual transmission [of HIV]. It is because they reached a certain level of prevention through PrEP [use], as well as prevention for people who inject drugs with harm reduction, with condoms, et cetera. A whole swathe of prevention messages and interventions, plus a very high ART coverage, [that is what] helped them achieve what they believe is less than 9 per 100,000 cases of new HIV, which is, for them, virtual elimination. I do not want to say that targeting is the only way to make things happen, and helping, whether it is subnational or national targets, around how much PrEP needs to be brought forward, or prevention brought forward, with a ratio with treatment, will help, perhaps, countries, ministries say, this is a key intervention to invest in, because it will help us to reduce new infections. We look at PEP, PrEP, and combining this with STI prevention is going to be important as we go forward.

Dr. Achrekar (UNAIDS): We are all at fault for not elevating prevention in the way that it needs to be elevated. We need to call for a prevention revolution or some such thing, because for the reasons we discussed here, our young people, they are not seeing HIV in the way that others did 20 years ago. At least at UNAIDS, and [through] what we are doing as part of the joint program, we are trying to elevate the need to focus on prevention, because we know that this [prevention], not at the risk of not closing the gaps of where these gaps in treatment exist, but prevention has fallen off the radar in some ways, and so we are really trying to elevate [the issue]. The options and choices are important. I fully agree that there is not a magic bullet for any of this. We have not even done the basics. We have not even done the basics right and well. Let us do that. Let us do that well, and part of it is also that data are important for this, because we need to make sure at the country level that we are tailoring interventions specifically for the populations where the transmission is happening for adolescent girls and young women, for example, in sub-Saharan Africa. We really need to be differentiated in how we are approaching prevention, so that it is not bought for everyone, but tailored for the specific populations in need.

Dr. Zuniga (IAPAC): Thank you to our panelists for such a robust conversation as we find ourselves challenged on the path towards attaining the 2025 targets and SDG 3.3. We have a track record of success upon which we can and must build, but the HIV response in 2024 and beyond requires re-focusing and re-energizing, with many of the recommendations made today as a foundation for our collective efforts. I turn to Vinay to say a couple of closing words before we end this enlightening Fireside Chat session.

Mr. Saldahna (UNAIDS): Thank you, panelists, for a very rich discussion. We have highlighted several priorities that we will be taking forward throughout the Continuum 2024 conference and let us see where these priorities land.